Tonight, people in Boston and New York City and possibly elsewhere celebrated Petrov Day. The holiday was created by Jim Babcock, for people who are concerned about developing technologies that might destroy humanity’s future – among them, nuclear war, climate change, bioengineered plagues and artificial intelligence.

This is intended for small audiences, up to about 8, and for people who are already familiar with the ideas behind the ritual.

In New York, we tried a few new ideas, deviating from the original script when we thought it appropriate. This article is a review of our execution of the holiday. I highly recommend you read the script for the ritual first, so you understand the context.

(Seriously, go read the script before continuing to read).

….

…ready?

Okay, here we go:

Overall Review

A common theme of rationalist holidays is “let’s go through the story of human progress and tell stories about.” When Jim started creating Petrov day, at first I worried “oh no, another holiday retreading the same ground.” But I think Jim did a much better job than anyone else I’ve seen, at telling that story well and making it emotionally significant.

Some of that emotional salience was lost due to technical snafus. I expect that to go better in future years. I also think there’s plenty of room to experiment and improve the ritual.

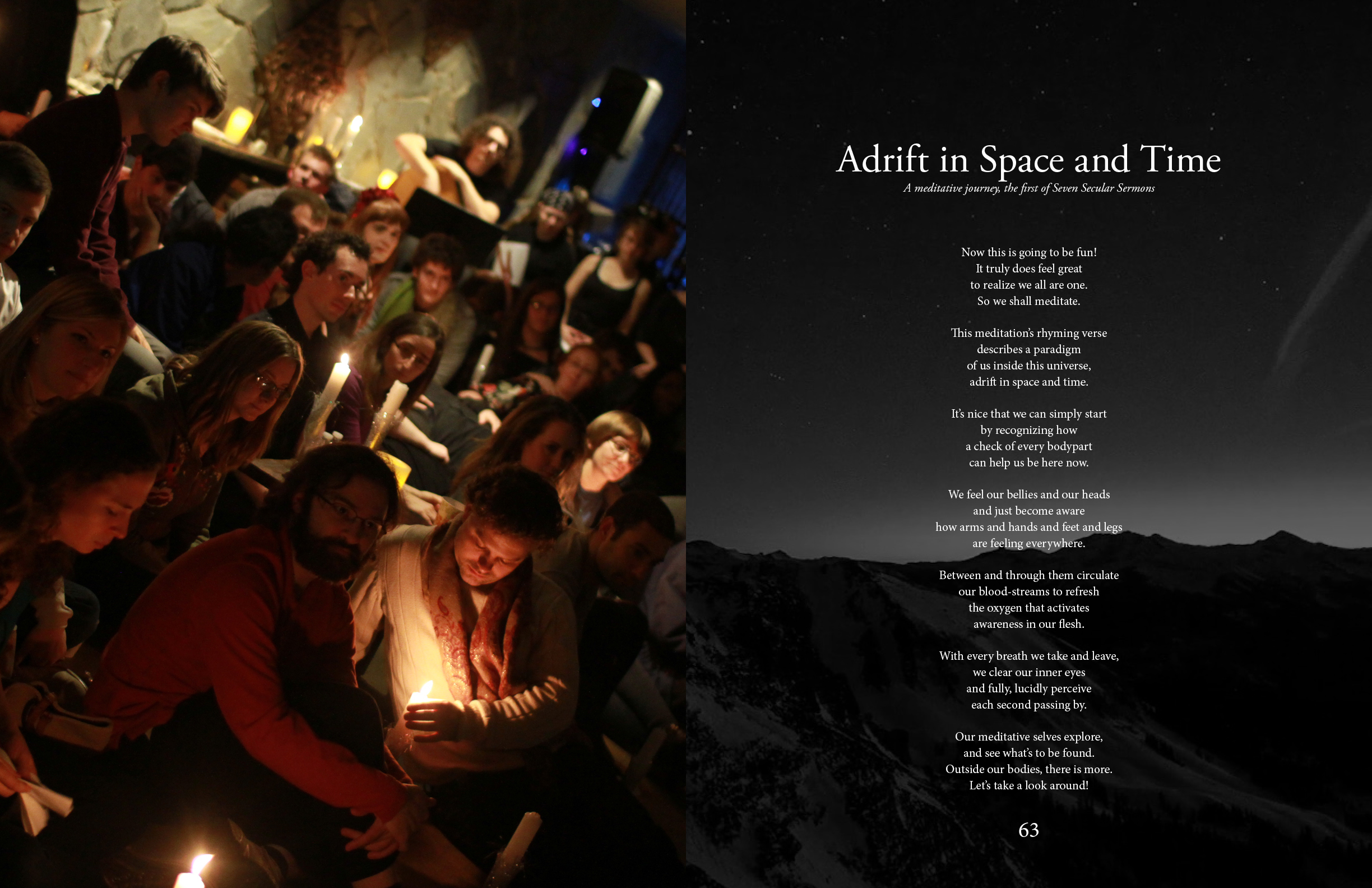

But it felt good to be surrounded by a small group of people that took the same ideas as me seriously. It was fun. It had dramatic tension both from intellectual content and from the literal dangers of the candles.

I do worry about ritualizing particular concrete ideas, as opposed to overarching values. Particular ideas can turn out to be less relevant than you thought they were, or in some cases be actually false.

At the same time, some ideas are important to take seriously, and ritual is a good tool for that. My tentative solution is to recommend people doing rituals like Petrov Day, but not necessarily doing them every year. Instead, I think we should develop a collection of rituals that have a similar overall theme (say, committing to help the future of humanity in concrete ways), but rotate which ritual you do each year, so we don’t get too attached to a particular execution of that theme (for example, Artificial Intelligence).

I’ll say more about this in a future blog post.

On to the technical points about the ritual, how we executed it, and how others might learn from our example.

Candles

The original script called for a menorah or similar candelabra, to hold 6 candles. Six of them symbolize human progress:

- The invention of fire

- The invention of agriculture

- The invention of writing

- The invention of the scientific method

- The invention of industry

- The invention of computers

And then, two final candles (traditionally set to the far right of the candelabra) that represent Friend and Unfriendly Artificial Intelligence – two potentially powerful technologies that could bring about great good or great harm to the world.

We didn’t have a menorah, so instead we made due with 6 tea candles. For friendly and unfriendly artificial intelligence, we used an empty candle holder stuff with matches.

We learned a few interesting things from that experiment:

- You need to light one candle with a previous candle (showing how, say, writing enabled the scientific method to develop). This can’t be done directly with tea candles, but we made do using additional matches that we lit from the previous candle, and then used to ignite the next one.

- Using a huge cluster of matches for AI was a very good innovation. At the end of the ceremony, you hold the candle of computation near the candle of AI – consciously highlighting the risk that humanity might invent a superintelligence, and then choosing not to. A concern of mine was that this would feel underwhelming. It’s meant to reflect the gravity of Stanley Petrov’s decision, but there’s no real temptation to light the last candle.By contrast, a giant swarm of matches is really tempting to set ablaze. We had each person hold a match near each of the two AI match-masses, and people were inching closer and closer, creating a moment that was fun while still intense, a good emotional climax to the evening.

- If you’re placing the candles in circle instead of a straight line (as on a menorah), it’s easy to get confused about which one is which. You can solve this by just using the traditional straight line, or marking your candles more distinctly.

- Make sure to have large enough candles that they don’t burn down during the ceremony. We had to replace one.

- The script calls for a fire extinguisher. A first aid kit would also be valuable. Someone accidentally burned themselves and missed part of the ceremony. This actually made the ceremony feel more interesting (even to the person that burned themselves), because it highlighted the potential danger in a very visceral way (without being genuinely dangerous – she’ll heal in a day or so). But having burn cream on hand would be worthwhile.

- On a related note – I gave everyone a glass of water before the ritual, so that if they got thirsty the ceremony wouldn’t be interrupted. I didn’t even realize that this doubled as additional fire safety (and place to put your fingers if they get burned)

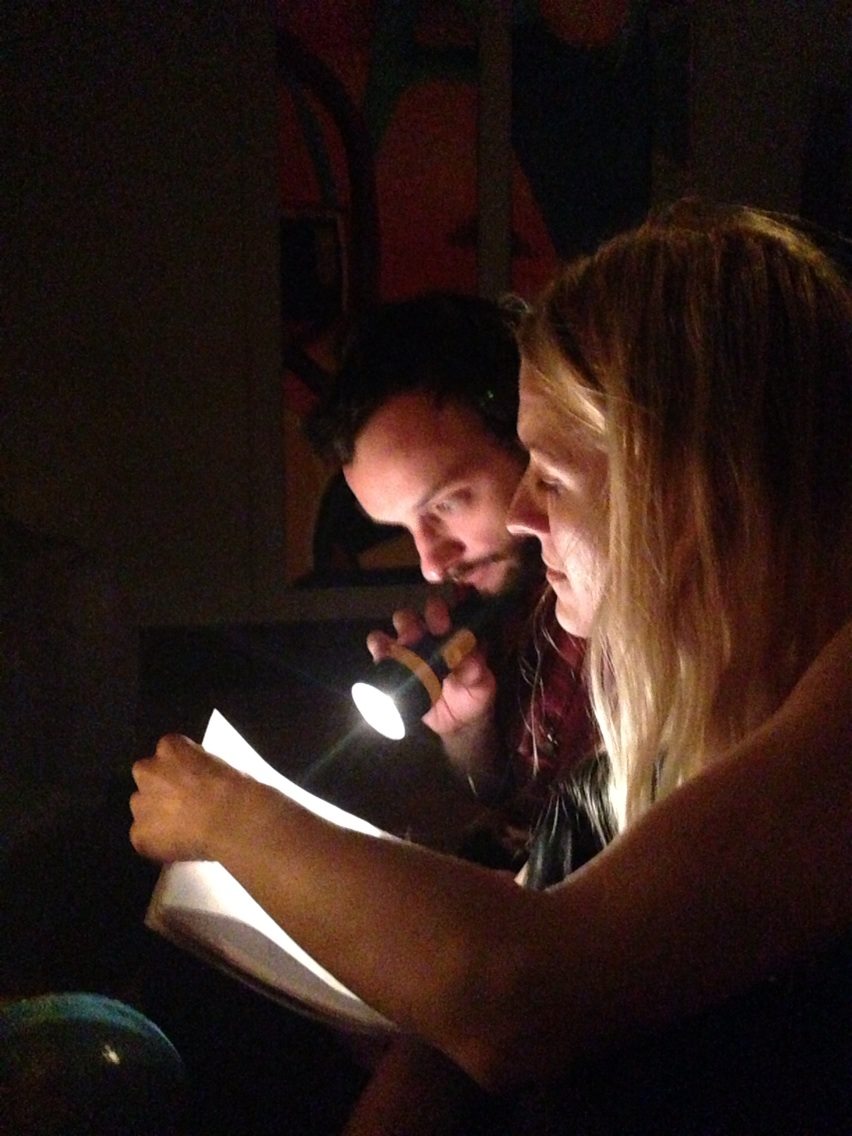

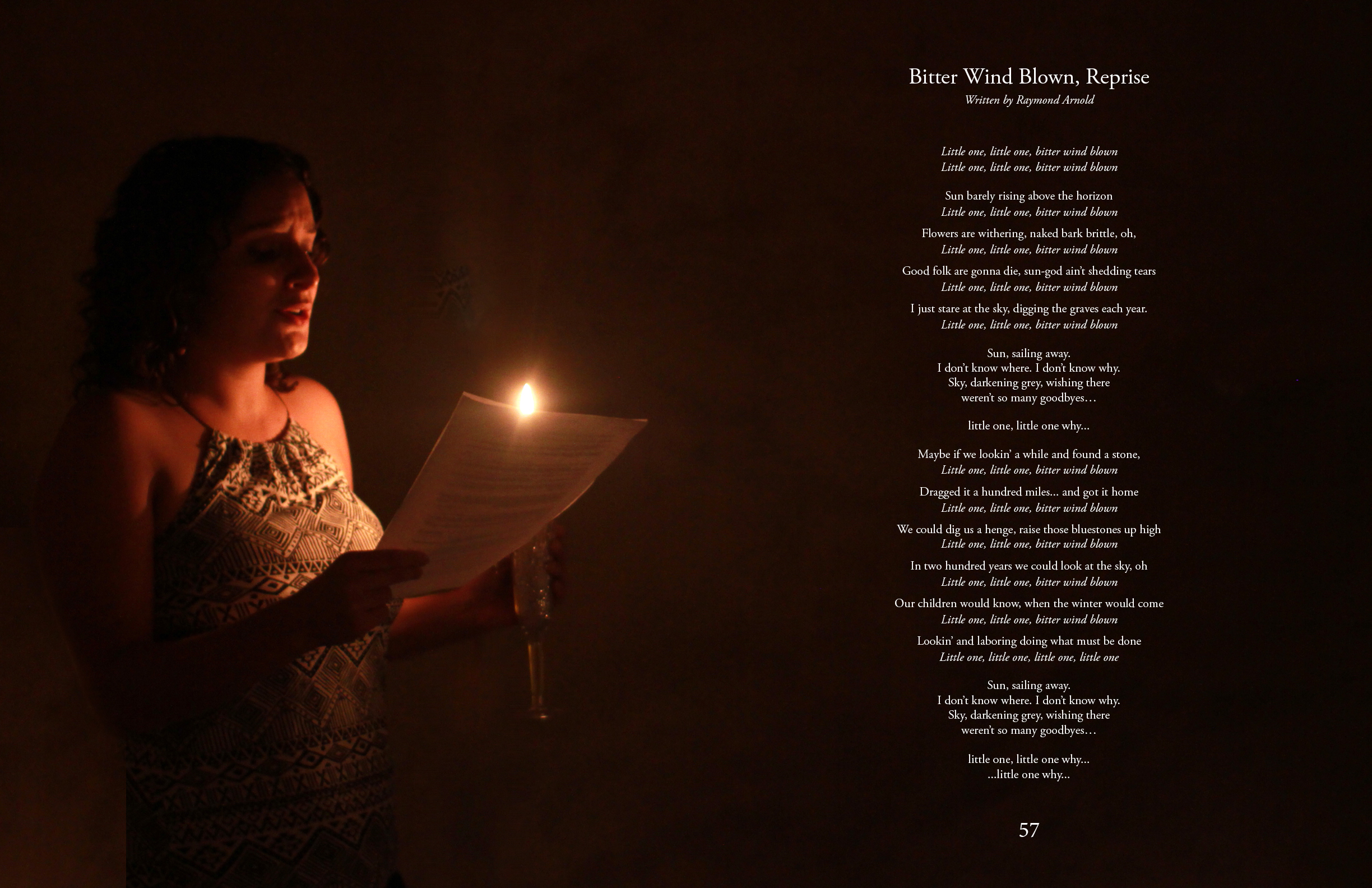

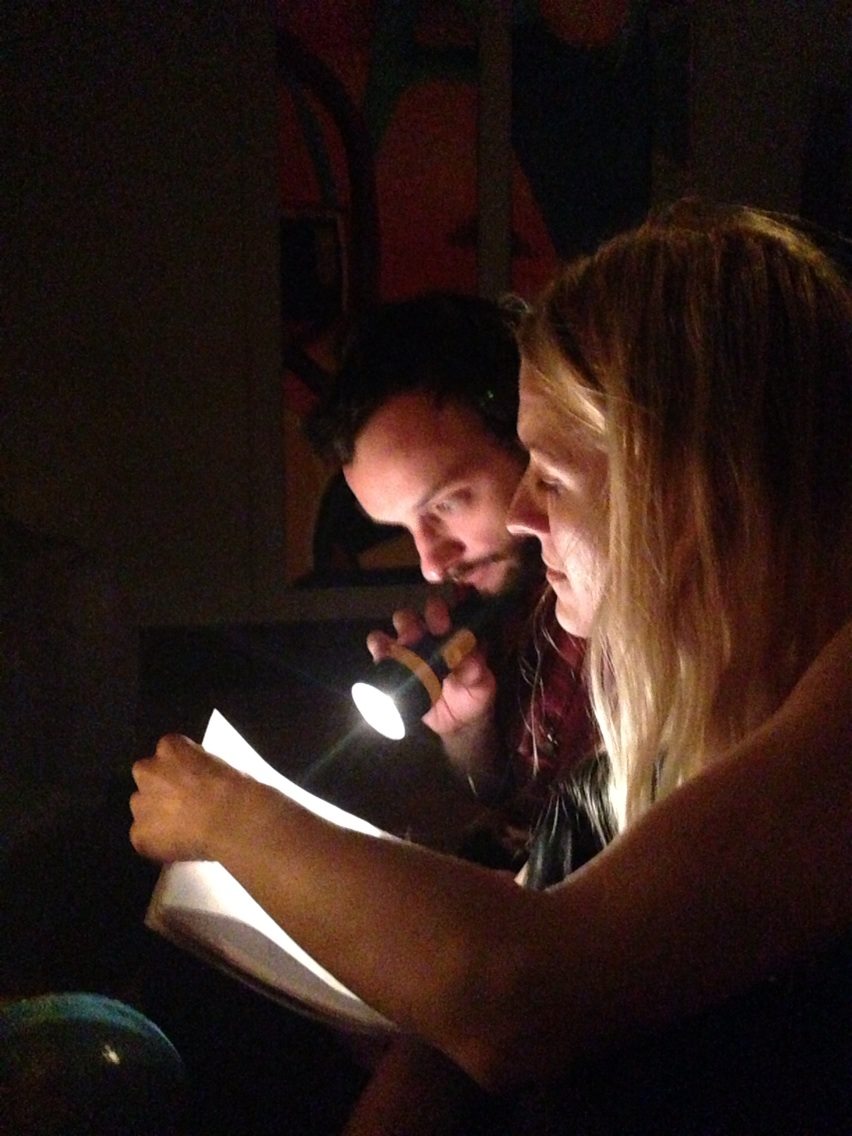

The Problem of Darkness

We conducted the ceremony at night, with the lights dim. It was hard to read from the book unless you were holding a flashlight, which we passed around, or a candle, which wasn’t always available.

We conducted the ceremony at night, with the lights dim. It was hard to read from the book unless you were holding a flashlight, which we passed around, or a candle, which wasn’t always available.

Not everyone read very clearly our loudly, so sometimes we had to strain just to hear what was being said, and it was hard to feel the emotion of some words because we were struggling just to understand them intellectually.

I’m not sure what a good solution is. The ceremony very much feels like it should be held in darkness. Raising the ambient light would diminish the mood. Giving everyone a flashlight might make the candles seem underwhelming. Using a projector (as I do in the Winter Solstice to solve this problem) isn’t really appropriate.

Suggested Changes

- The booklet says not to read the italicized sections that describe actions to take (such as “take the candle that symbolizes industry, and use it to light the candle of computation“). But since it’s dark, and since different people read at different speeds anyway, I think it’s better to read that all aloud. That way it’s clear what’s symbolizing what, and the pacing of the event is more consistent. (The most important instance was when someone dropped three drops of wax on our cherished memories, and most people didn’t even notice)

- The script suggests that just one person holds a candle near the AI candles. I think it makes for a better, more participatory ending for everyone to hold matches up to it (and again, to use a giant array of matches that look like they’ll explode awesomely if lit) ((while making sure to have adequate fire safety if things go wrong, of course))

- ((Actually, it may be correct not to actively encourage random people acquiring the script to do slightly more dangerous things, since random people on the internet may not read all the instructions or take enough precautions. But I think it’s a good idea for groups that have taken the time to prepare and be safe to add an element of (mild) danger))

- A few sections call for a candle to pass around. I think it should be highlighted that the candle should be passed around slowly, deliberately, taking time to experience what the candle represents.

- Many of the quotes begin with long, technical language, that makes them hard to understand. After you read the name/date at the end of the quote, it’s clear what’s being talked about. But this means the first half of each quote is spent trying to figure out what’s going on, instead of being emotionally affected by it. I think a simple solution is to begin each quote with the name and some context. (Keeping it mysterious until the end is sort of cool if you’re reading it, and can go back and reread it. But a ritual of spoken words doesn’t work that way, especially when it’s conducted in the dark and is hard to see)

New Innovations

We tried a few new things, most of which went well:

We tried a few new things, most of which went well:

- We had an ornate hourglass in the center of the altar. The ceremony takes a bit under an hour to complete. However, if you don’t know what you’re doing and stumble through some parts, or if the ceremony is interrupted, it’s plausible we could fail to complete it in time. The visual reminder adds a sense of urgency.

- Soundtrack – we conducted the ceremony alongside the soundtrack of Tron Legacy, which turned out to be a very good fit. Not only is the general “ambient orchestral techno” a good atmosphere for a story of human progress and dangers of technology, but the soundtrack very nicely synced up with the content of the event. Sad music started playing when we read about the Black Death. Exciting techno beats began right as we got to the rapid progress of science. Ominous music began playing as we led up to world war 2, and hit a crescendo right as we read a quote from Hitler.

- We stumbled a bit during the ceremony. If we hadn’t stumbled, we would have completed the ceremony right as the soundtrack ended. Instead we were late by a few minutes. This prompts an idea:

Petrov Day always seemed to me like it should have risk of failure. So here’s my proposal for that: Use a soundtrack of similar length (about 45 minutes), and an hourglass.

If you take longer than an hour, the ritual fails, and you get the “bad” ending – you light the candle of Unfriendly Superintelligence.

If you complete it in under an hour but after the soundtrack finishes, you get the neutral ending (neither of the two candles are lit)

If you complete it during the last song of Tron Legacy you get the best ending: light the candle of Friendly Superintelligence.

But we don’t want to encourage people to rush through the ceremony without feeling the meaning of the words, so if you complete it before the last song of Tron, you also get the bad ending (which is appropriate, since rushing ahead with technology is the exactly the thing we’re concerned about).

This is obviously gameable (you can rush a bit, and then slow down at the end if need be), but I think the emotional incentives are actually pretty good. If you rush too fast, you’ll lose… but losing is actually pretty cool too (you get to light a giant conflagration of matches), so you’re not really motivated to cheat. But winning is just hard enough to make you feel proud to win or get the neutral ending.

Celebration

After the ritual, we all felt like we had won, and wanted to celebrate. We also really wanted to destroy something, having just painstakingly not set a crazy tower of matches on fire, and that needed an outlet.

As it turned out, we had a recently completed Earth Puzzle

What we ended up doing was tossing the puzzle ball in a circle, hot potato style. We started singing the chorus of my song “Move the World”, and then started chanting it faster and faster and tossing the ball faster and faster until it fell apart.

This… in some ways goes against the entire spirit of the event. But it was super fun, which is probably more important. (One could create a new chant that gradually escalates to somehow talking about the world being turned into computronium, which can be either good or bad, which may make for a reasonably cathartic ending).

It also suggests a before-the-event-activity: slowly putting a world-puzzle together. (You can leave the puzzle out on the table as your guests arrive, surrounded by cheese and crackers and some light music for a pre-Petrov Day hangout).

We also felt, more generally, that we needed more good music after the event. Someone spontaneously started singing:

We got the whole world, in our hands…

With subsequent verses improv’d:

We got the whole future, in our hands

We got the Moon and Mars, in our hands

We got the solar system

We got the local cluster

We got the Milky Way

We got the whole light-cone

It’s the sort of thing that sounds really lame and childlike, but honestly fit the occasion perfectly and felt really fun.

Then we sang “we will rock you” because we were feeling epic.