This is the text used at the 2015 NYC Solstice, the during the Nightfall section. Originally this was performed and written by Raymond Arnold and Lyz Liddell, though it can be adapted for others.

Speaker 1

The year is 1940. My name is Noel Regney, and the Germans have just invaded my country. Close friends of mine are dead. I have been drafted into the Nazi army against my will. Forced to wear their uniform. Forced to do things I am not proud of.

But I find ways to keep fighting for my country. From within Nazi ranks. I work as a spy for the French Resistance. And eventually, I arrange an ambush. My company falls into my trap. In the crossfire I am shot. But I survive, and I flee here, to Manhattan.

And in this new country, I begin to build a home. I join a Unitarian Universalist church. I marry a woman named Gloria with a voice like an angel, and we begin to write music together. Our songs play on radios across the country.

In 1942, my new country drops a bomb on Hiroshima.

And just like that, fifty thousand people are dead.

That’s the sort of thing that can happen, suddenly. Just like that.

In the wake of that explosion, a new kind of cold settles over the world. Radios and televisions across the country begin to tell stories about a possible apocalypse. My children are taught that if a nuclear strike is launched, they should push their desk against the wall and squat beneath.

We know that squatting beneath a wooden desk isn’t actually going to help, but we pretend like it does.

It’s something to do. It’s better than nothing.

Speaker 2 (Lyz Liddell)

The year is 1962, and my name is Vasili Arkhipov. I am an officer in the Soviet Navy.

The United States has put nuclear missiles in Turkey, in range of my country. To counter, my Russian leaders put nuclear missiles in Cuba, within striking distance of the US. The Americans bare their teeth. We raise their hackles. The hairs on our necks stand on end.

Our leaders and theirs want to de-escalate, but our militaries have thousands of moving parts. The labyrinth of game theory and politics we’ve woven around ourselves seems impossible to escape.

My submarine is off the coast of Cuba, and we’ve just lost contact with Moscow. My Captain and his third in command believe that nuclear war has already begun. They want to launch our nuclear torpedo in retaliation. My Captain is ready. His hand hovers over the button.

As Second in command, my authorization is needed to strike. I believe that too much is at stake. I argue, fiercely, that we must wait, that we must surface and seek further orders. Tempers rise. Everyone yells. But in the end, the captain listens. We wait.

In the morning, the sun rises. Hiding in our silent ship, we still don’t know what’s happening on the surface. We’re dripping sweat. But the world turns, and humanity lives on. For now.

Speaker 1

In Manhattan, I go to work each morning – my coworkers and I listen to the radio all day, waiting for an announcement that everything is about to end. I walk home each night, silent.

I go to sleep beside my wife and children, uncertain whether I’ll wake up the next day. But each morning the sunlight keeps spilling through the window curtain.

I walk home for the third time that week. It’s cold October night. There’s a star shining bright above me and I want to find it beautiful but all I can think about missiles flashing in the sky, and I feel so powerless and alone.

And then I round a corner.

And I see two women. Each is pushing a stroller, and in each stroller is a baby. The two children look at each other. And they smile. And they laugh. And they have no idea what’s happening.

And in that moment, a song comes to me, lyrics forming in my head as fast as I can think them. I arrive home and share it with my wife. And she sits at the piano and writes a melody and then we start singing. And we can’t sing it all the way through without breaking down sobbing, but we hold each other and try again.

The song is written in the language of the Christian stories. But the plea is universal. A desperate hope that thousands of confident ideologies, economic doctrines and religions could find a way to coexist, in a world where they had the power to destroy each other.

…

[One of the candles is extinguished. Speaker 1’s mannerisms change to his usual self]

The year is 2013. My name is Raymond Arnold, and I’m listening to the song Do You Hear What I Hear. I’m reading about a week in human history – where one man on a submarine stopped a nuclear war. Where another man in manhattan wrote a desperate plea for peace, that people promptly misinterpreted and ignored.

And I’m noticing, that the song was about the birth of a story.

The story is born, like all of us, small, and powerless. Whispered by the night wind to the humblest of creatures. But each person it touches, it helps to become stronger, and wiser. And they in turn help the story to evolve – to become more useful, and more powerful.

The story gives a shepherd boy the courage to walk before a king and demand his attention. It gives the king the humility to listen, and to learn.

And then, having reached the ear of the king, the story changes the world.

And it occurs to me, that the lyrics to this song are, in fact, incredibly open ended. From its birth, this song has been steeped in metaphor, and evolving interpretation.

So I would like us to sing this song together, in honor of those two children, on that cold october night, who woke up the next day. Who lived to grow old. Who, one way or another, brought a little more light to the world.

[Do You Hear What I Hear is sung, transitioning into a faint reprise of Bring the Light.]

Speaker 2

The year is 1989. My name is Elizabeth Liddell, and I am about to turn 8 years old. I’m coming down the stairs to the living room, where Dad’s watching the evening news, as usual. “Wait a minute,” he says. “Come watch this.” He points to the TV, where I see a group of teenagers with mohawks and studded leather jackets taking sledgehammers to a vertical slab of spray-painted concrete. I watch for a few minutes, and then I wander off. I didn’t really know what was so important about those teenagers that Dad felt I should stop and watch, but I remembered it.

To this day, I remember watching that clip of the news, watching what I now understand were German teenagers helping to tear down the Berlin Wall at the end of the Cold War. My father, who had lived through the Great Depression, Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and the Cold War, recognized the monumental importance of that event, and made sure his daughter stopped and took note – even if I was too young to understand at the time.

History is a funny thing.

The same terrifying game theory that led us to the brink of nuclear war, also led us to a new frontier.

The US and the Soviets didn’t go to space for the noblest of reasons. It’d be nice to claim we did it for science, or for the adventure. But mostly, the space program is just one more weapon in our ideological war.

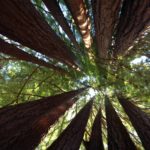

But it’s interesting. Once humanity finally got to space, we turned around, and we saw that.

[Gestures to the a video of the earth from space, camera slowly pulling away to reveal the Pale Blue Dot photo]

And for the first time, anyone making a plea for peace, anyone desperately begging for people to put aside their grievances and protect their home, has a symbol they can point to, and say:

Look at that.

That’s here. That’s home. That’s us.

On that dot is everyone you love, everyone you know,

Everyone you ever heard of,

Every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.

The aggregate of our joy and suffering.

Thousands of confident religions, ideologies and economic doctrines.

Every hunter and forager

Every hero and coward,

Every creator and destroyer of civilization.

Every king, and peasant.

Every young couple in love.

Every mother and father,

Hopeful child

Inventor and explorer.

Every teacher of morals.

Every corrupt politician.

Every “superstar”. Every “supreme leader.”

Every saint and sinner in the history of our species,

lived there,

on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast, cosmic arena.

Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors,

so that in glory and triumph,

they could become momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.

Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel,

on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner.

How frequent their misunderstandings.

How eager they are to kill one another,

How fervent their hatreds

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance

The delusion that we have some privileged position in the universe,

Are challenged by this point of pale light.

Our planet is a lovely speck, in the great enveloping cosmic dark.

In our obscurity, in all this vastness

There is no hint that help will come from elsewhere,

To save us from ourselves.

The earth is the only world known, so far, to harbor life.

There is nowhere else, in the near future, to which our species could migrate.

Visit, yes. Settle, not yet.

Like it or not, for the moment, the Earth is where we make our stand.

[The last candle is extinguished]